The Effects of Restricted Physical Activity on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Depression

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The objective was to identify restricted physical activity in patients with depression, and to determine the effects of that restricted activity, on their health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Methods

Data was analysed from Year 1 of the 7th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII-1). From a total sample of 8,150 subjects, 277 adults aged ≥19 years who were diagnosed with depression were selected. The results were derived using restricted activity and HRQOL data measured from the subjects.

Results

Most of the participants were females ≥ 50 years old. HRQOL scores were high in the “self-care” dimension and low in the “pain/discomfort” and “anxiety/depression” dimensions. Their restricted activity due to illness in the past year, led to increases in participants being bedridden or absent from work. Many participants reported being bedridden for more than 3 months. A higher number of absences owing to illness in the past year, and longer durations of being bedridden, had a negative impact on HRQOL. Age, marital status, educational level, income level, and occupation were the sociodemographic variables that had an impact on HRQOL.

Conclusion

Patients with depression experiencing stress in their daily lives should take measures to avoid illness and pain that may lead to them becoming bedridden, and employ lifestyle habits with support from families and community health promotion centres, where mental health counselling can be accessed.

Introduction

Depression is a common mental health disorder, with a worldwide lifetime prevalence in adults of 5%–12% in males, and 10%–25% in females [1]. Depression contributes to the development of chronic diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes causing serious functional impairment for the individuals concerned, and increases utilisation of health care services and public health burden [2].

Patients with depression often lack confidence, have a noticeable pattern of wanting to be alone, and may lose the will to live. Moreover, because of clear physical symptoms, such as weight loss, loss of appetite, digestive impairment, headaches, and sleep impairment, patients have a difficult time concentrating on any tasks at hand [1]. In addition, people with depression have a negative image of themselves, and have negative thoughts about their future [3]. An increase in the severity of depression can lead to suicide from repeated thoughts about death [4]. Furthermore, depressive episodes can cause problems in maintaining social relations, and hinder effective job performance, ultimately leading to a decline in the quality of life (QOL) [5].

Various activities, including social activities, are known to have a positive impact on mental health. By engaging in activities of different kinds, humans find their identity, maintain social relations, and feel a sense of belonging and self-efficacy [6]. One of the theories about behaviours that cause a recurrence of depression is “learned helplessness.” According to Seligman [7], depression is caused by a sense of helplessness in controlling the outcome of a situation. Depression causes limitations in activities, and the inability to perform activities causes the person to perceive him/herself as helpless, which, in turn, causes the person to fall further into depression. Ultimately, restricted activity creates a vicious cycle that prevents the person from recovering from depression, which consequently leads to a decline in QOL.

The World Health Organization defines QOL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of their culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.” It is a broad concept that is affected in various ways by an individual’s physical health, mental state, level of independent living, social relations, and relationship with the environment [8]. QOL is directly linked to one’s happiness and achievement of life goals, and it is very important in identifying success in the life of an individual. In other words, it can be viewed as having the utmost importance in the general well-being of an individual [9]. In particular, health-related QOL (HRQOL) is used as an indicator of health and well-being which directly impacts on the physical, psychological, social, and mental health of an individual [10].

Recent studies of depression in the elderly have focused mostly on secondary depression that has been diagnosed following a pre-existing disease or previous depression. There are many studies on depression and QOL, whilst very few studies have examined the restricted activity that results from depression, and how this affects HRQOL. The present study used nationally representative data [Year 1 (2016) of the 7th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII-1)] to identify restricted activity in patients with depression, and examined what type of restricted activity had an impact on HRQOL, and which characteristics were associated with HRQOL. This study also aimed to provide data to help establish guidelines for managing the health of patients with depression.

Materials and Methods

1. Participants

Data from the KNHANES VII-1 was used in this study after review, and approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. For the sample population to be representative of the entire Korean population, weighted values were assigned to each region. From a total sample size of 8,150 individuals, 277 adults aged ≥ 19 years who had been diagnosed with depression were selected.

2. Measuring instruments

2.1. HRQOL

The instrument used to measure HRQOL was the EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) Index, which is a multidimensional preference-based HRQOL measure. It is a useful instrument with objectivity and reliability for measuring HRQOL that can be used in various situations. It shows the tested results as a simple health profile, or a numerical utility value [11,12]. The EQ-5D Index consists of items that ask about current health status in 5 dimensions; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each of the dimensions has 3 levels: 1 point for “no problem,” 2 points for “some problems,” and 3 points for “serious problems.” The present study calculated the scores using the estimated weight for Koreans presented by the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The calculated scores represented the overall HRQOL whereby lower scores indicated a higher HRQOL [13].

2.2. Activity limitation

The present study used survey data on whether current health problems caused any limitations in daily and social activities. The items surveyed included being bedridden owing to illness in the past month, the number of bedridden days owing to illness in the past month, being bedridden owing to illness in the past year, the number of bedridden days owing to illness in the past year, being absent from work owing to illness in the past month, the number of absences owing to illness in the past month, being absent from work owing to illness in the past year, and the number of absences owing to illness in the past year.

3. Statistical analysis

Collected data were analysed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The sociodemographic characteristics and restricted activity of the patients with depression were analysed by descriptive statistics. The effects of general characteristics and restricted activity on HRQOL were analysed using multiple regression analysis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

1. Participant characteristics

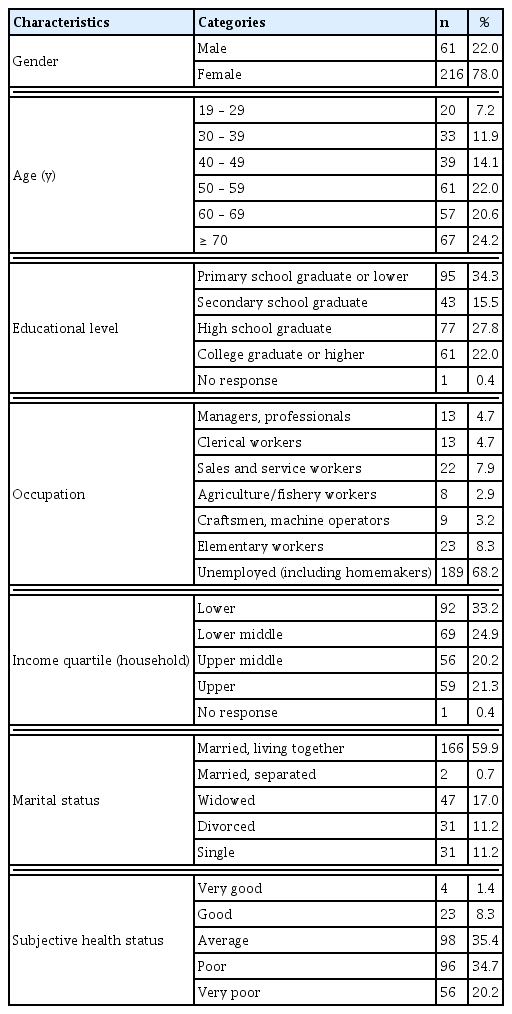

There were more females (78.0%) than males (22.0%), while the highest number of participants according to age group were ≥ 70 years (24.2%), 50–59 years (22.0%), and 60–69 years (20.6%). For educational level, “primary school graduate or lower” (34.3%) was the most common response, followed in order by “high school graduate” (27.8%) and “college graduate or higher” (22.0%). For occupation, “unemployed, including homemaker” (68.2%), was the most common response, followed in order by “manual labourer” (8.3%) and “service/sales worker” (7.9%). With respect to income level, the incidence of lower income participants was 33.2% and lower-middle was 24.9%, showing that those with an income level below middle, accounted for more than half of the sample. For marital status, living with a spouse (59.9%) was the most common response, followed in order by widowed (17.0%), divorced (11.2%), and single (11.2%). For subjective health status, those who perceived their health to be poor or very poor (54.9%) accounted for more than half of the sample (Table 1).

2. Score of HRQOL

HRQOL (EQ-5D Index) results were as follows: each dimension showed scores in the range of 1.3–1.5 points. With respect to each dimension, pain/discomfort showed the lowest HRQOL with 1.58 ± 0.67 points, whereas self-care showed the highest HRQOL with 1.17 ± 041 points (Table 2).

3. Status of suicidal ideation and restricted activity in patients with depression

The status of restricted activity in patients with depression was as follows. There were 63 subjects (22.7%) with experience of being bedridden owing to illness in the past month, among whom being bedridden for < 3 days (49.2%) was the most common response. There were 119 subjects (43.0%) with experience of being bedridden owing to illness in the past year, among whom being bedridden for < 7 days (42.0%) was the most common answer, while many also responded with “8–30 days” (29.4%) and “> 90 days” (15.2%). Meanwhile, only 5.4% of the subjects responded “Yes” to being absent from work owing to illness in the past month, with most indicating < 3 days of absence. There were 35 subjects (12.6%) with experience of being absent from work owing to illness in the past year and their most common response was being absent for < 7 days (65.7%).

The proportion of those who had planned suicide in the past year was 10.1%, while the proportion of those who actually attempted suicide was 5.4%. The proportion of whole study population who had received psychiatric counselling in the past year was 38.3%, which was lower than the proportion of those who had not (Table 3).

4. Effects of restricted activity and sociodemographic characteristics on HRQOL

The main objective was to examine the effects of restricted activity on HRQOL, while sociodemographic characteristics were additionally examined to provide further details into potential underlying factors. To examine such effects, multiple regression analysis was performed. Being bedridden owing to illness in the past month (β = 0.299, p < 0.001), being bedridden owing to illness in the past year (β = − 0.161, p < 0.05), being absent from work owing to illness in the past year (β = − 0.237, p < 0.05), and the number of absences owing to illness in the past year (β = − 0.173, p < 0.05) were found to have an impact on HRQOL. Among the sociodemographic characteristics, age (β = − 0.272, p < 0.001), educational level (β = 0.283, p < 0.001), income level (β = 0.288, p < 0.001), and occupation (β = − 0.218, p < 0.001) were found to have an impact on HRQOL (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study used KNHANES VII-1 (2016) data to examine restricted activity in adult patients with depression, and analysed the effects of such restricted activity on HRQOL. With respect to the general characteristics, there were 3 times as many females as males who were diagnosed with depression. The lifetime prevalence of depression has been reported to be higher in females, increasing in incidence after menopause [14]. In the present study, more than half of the subjects were 50 years or older, and it was determined that the incidence of adult depression was high among women, especially those aged 50 years or older. Those women whose education level were “Primary school graduate or below” were the most common, while “unemployed, including homemaker,” was the most common response for occupation. With respect to income level, more than half of the subjects gave the response of “lower” or “lower-middle” income level. A study by Kim [15] reported that economically vulnerable or unemployed women showed a decline in HRQOL because they do not have personal savings or the financial wealth to enjoy leisure, leading to increased susceptibility to depression.

With respect to the distribution of HRQOL scores, the scores for the self-care dimension were high, whereas the scores for pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were low. Patients with depression can independently perform activities of basic living, such as self-care, but they experience difficulties in uncomfortable situations involving physical pain or emotional states such as anxiety. Depression can trigger anxiety and extreme thoughts [16] by causing chronic pain [17], stress, and a negative perception of life.

With respect to restricted activity in patients with depression, 22.7% had < 3 days of being bedridden owing to illness in the past month, but almost half (49.2%) had experienced being bedridden as a result of illness in the past year, with many cases resulting from being bedridden for over 3 months. There were more cases of being absent from work owing to illness in the past year than in the past month. Although depression may appear as a single episode, it has a strong tendency to recur regularly. A single episode is usually known to last 3–6 months, but if depression becomes more severe or progresses, it becomes difficult to maintain one’s daily life and job because of fatigue, loss of appetite, helplessness, and insomnia [1]. Preventing depression is of the utmost importance, but if it does occur, preventing its recurrence and shortening the duration of episodes becomes critical. Since there were 15 subjects who had attempted suicide in the past year, it is necessary to provide preventative measures for suicide attempts by patients with depression. Among the subjects of the present study, close to twice as many subjects did not receive psychiatric counselling as those who did, indicating that the counselling rate among patients with depression is low. Currently in Korea, depression is included in the list of mental illnesses for which the patient can receive counselling. However, because of low public awareness about mental illnesses, there are many people who are afraid of being stigmatised if they are diagnosed and have to visit hospitals. In Korea, mental health promotion centres have been established and are in operation in various communities to provide psychiatric counselling and treatment for people who are burdened by the high cost of counselling at hospitals. Currently, there are about 190 such mental health promotion centres in Korea, where depression prevention, counselling, and rehabilitation programmes are being conducted [18]. It is important to promote participation in such agencies so that patients receive active treatment. The programs in these institutions may include creative activities such as art therapy, cooking, music therapy and sports, promoting physical exercise and social adaptation training as therapeutic strategies for treating depression [19].

Examination of the effects of restricted activity on HRQOL showed that being bedridden owing to illness in the past month, being bedridden owing to illness in the past year, being absent from work owing to illness in the past year, and the number of absences owing to illness, all had an impact on HRQOL. Longer durations of being bedridden and being absent from work owing to illness resulted in greater declines in HRQOL. A study by Kim [20] reported that chronic diseases impact HRQOL by causing financial difficulties because of continued medical costs. In addition, longer durations of being bedridden lead to a decline in the ability to perform daily living activities and social participation. Moreover, sociodemographic characteristics of HRQOL such as age, marital status, educational level, income level, and occupation, were all found to have an impact on HRQOL. A study by Kim and Suck [9] reported that HRQOL was associated with socioeconomic factors, such as educational level, income level, and occupation, as well as the presence or absence of a social support system, such as the number of children and having a spouse. Therefore, what is required is not only overall health management and lifestyle changes, but comprehensive pre-emptive efforts at the national level. More than half the subjects in the present study were homemakers or unemployed, and to improve their HRQOL, it would be necessary to explore measures to actively promote social participation. Santiago and Coyle [21] reported that leisure activities by home-bound elderly not only improved their physical functioning, but also improved HRQOL by building expectations that they could independently perform activities of daily living. Even if they do not have jobs, it would be desirable for them to participate in leisure activities or social gatherings, form close relationships by building networks, and/or participate in various programs operated by nearby public welfare centres or social support facilities.

Based on the findings of the present study, the following points may be considered. Patients with depression need systematic leisure programs and professional education for managing stress and depression continuously in their daily lives. Family and community support are needed for changing lifestyle habits to allow active movement to consistently manage the body for the prevention of pain and making sure that it does not lead to being bedridden. They should not be hesitant in visiting community mental health promotion centres for receiving psychiatric counselling, and for this, the encouragement and help of family members would be needed.

The limitations of the present study include the following. Since the only data used were from 2016, they did not reflect recent trends. In addition, since only previously assessed results were used, the study could not examine more dimensions associated with HRQOL. However, the study identified the status of restricted activity in patients with depression and how it affects HRQOL. Therefore, the present study may have significant value in establishing future national and community-based strategies for managing the health of patients with depression.

Conclusion

HRQOL scores were high in the self-care dimension and low in the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions. Examination of the effects of restricted activity on HRQOL showed that being bedridden owing to illness in the past year, being absent from work owing to illness in the past year, a higher number of absences owing to illness in the past year, and longer durations of being bedridden or being absent from work owing to illness, all had an impact on HRQOL. For patients with depression to continue to manage stress in their daily lives, not becoming bedridden because of illness, and preventing pain, may require constant support from family and the community to help change their lifestyle habits. Moreover, they should not pay attention to prejudices about mental health counselling and visit counselling agencies, such as community health promotion centres, to prevent extreme situations, such as suicide owing to depression.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the help from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to conduct the study using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.