Effects of Smoking Cessation Intervention Education Program Based on Blended Learning among Nursing Students in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to evaluate whether a “smoking cessation intervention” education program based on blended learning, was effective in improving nursing students’ perceived competence and motivation to perform a smoking cessation intervention for smokers.

Methods

A quasi-experimental, pretest–posttest design was conducted. The smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning, was administered to the experimental group (n = 23) in 5 sessions, consisting of 2 courses of an e-learning program and 1 course of a face-to-face learning program per session. The control group (n = 21) received the opportunity to participate in an e-learning program as well as receiving material of a face-to-face learning program, after completion of the smoking cessation intervention education program.

Results

The experimental group showed significant differences in autonomous motivation (t = −6.982, p < 0.001), controlled motivation (t = −3.729, p = 0.001), and perceived competence compared to the control group (t = −3.801, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

This study showed that a smoking cessation intervention education program adopting blended learning, was significantly effective in enhancing nursing students’ autonomous motivation and perceived competence to conduct a smoking cessation intervention. Further studies are needed to confirm longitudinal effects of this program.

Introduction

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. In South Korea, smoking-attributable mortality comprised 34.7% of total mortality in 2012 and smoking was thought to be responsible for 41.1% of cancers and 33.4% of cardiovascular disease cases in males [1]. However, smokers often have difficulty quitting and maintaining abstinence. Nearly 80% of smokers report that they would like to quit smoking, but because attempts to stop smoking are mostly unsupported, just 3%–5% of smokers quit successfully [2]. Nurse-delivered smoking cessation interventions have been effective for quitting smoking in various settings [3]. However, most nurses are reluctant to perform interventions because they are not motivated enough to intervene and may lack the necessary confidence to effectively support smokers. This may be triggered by a lack of exposure to standardized, smoking cessation intervention education programs because of lack of time and attention during undergraduate nursing education [4].

The World Health Organization has recommended that smoking cessation content be a required curricular element in nursing education [5]. Despite the educational importance of smoking cessation interventions, even though the clear majority of undergraduate nursing programs provide education about the harmful effects of smoking, few programs teach students how to help smokers to quit [6]. Therefore, smoking cessation interventions should be a part of standard nursing care and need to be incorporated into nursing education. It would be helpful if nursing students could acquire the competence and motivation needed to perform smoking cessation interventions, prior to the clinical practice, through adequate didactic and practical smoking cessation intervention education programs [7].

Results from previous studies indicate that adopting evidence-based smoking cessation intervention education programs, positively influences nursing students’ intention to engage in smoking cessation interventions, as well as improve their skills and confidence [7,8]. Self-determination theory (SDT) provides a framework for this study to explore motivation and perceived competence, and an educational intervention that can target the fundamental motivational processes of nursing students to intervene with smokers [7,9]. A previous study exploring the effect of SDT-based interventions on the adoption of new health-related behaviors, such as smoking cessation, suggest that the optimal motivational profile for sustained behavior change, has high autonomous motivation and high perceived competence [10]. Three constructs of SDT (perceived competence, autonomous motivation, and controlled motivation) can help explain the relationship between an individual’s perception of their abilities, and their intention to either perform or not to perform a smoking cessation intervention [7,11].

In terms of learning methods, blended learning with a systematic integration of traditional face-to-face engagement and e-learning, can give a greater flexibility in the teaching and learning process [12]. There is evidence to suggest that a blended approach to clinical education has the potential to address the needs required for healthcare graduates to perform competently in practice [13]. Also, this allows educators to overcome the competing demands for didactic and clinical time in undergraduate nursing education [14]. If a suitable smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning is provided to students who enter the nursing profession, it can help them to become competent at applying smoking cessation interventions in various settings, and the motivation to provide such interventions to smokers.

However, few studies have focused on the effect of developing a standardized smoking cessation intervention education program for nursing students in South Korea, and only 1 study has evaluated the effect of a simulation-based program in the absence of a control group [8].

Therefore, it is a essential to evaluate a smoking cessation intervention education program that can be standardized and included as an evidence–based program in the nursing curriculum. This study aimed to evaluate whether a smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning, was effective in improving nursing students’ perceived competence and motivation.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design

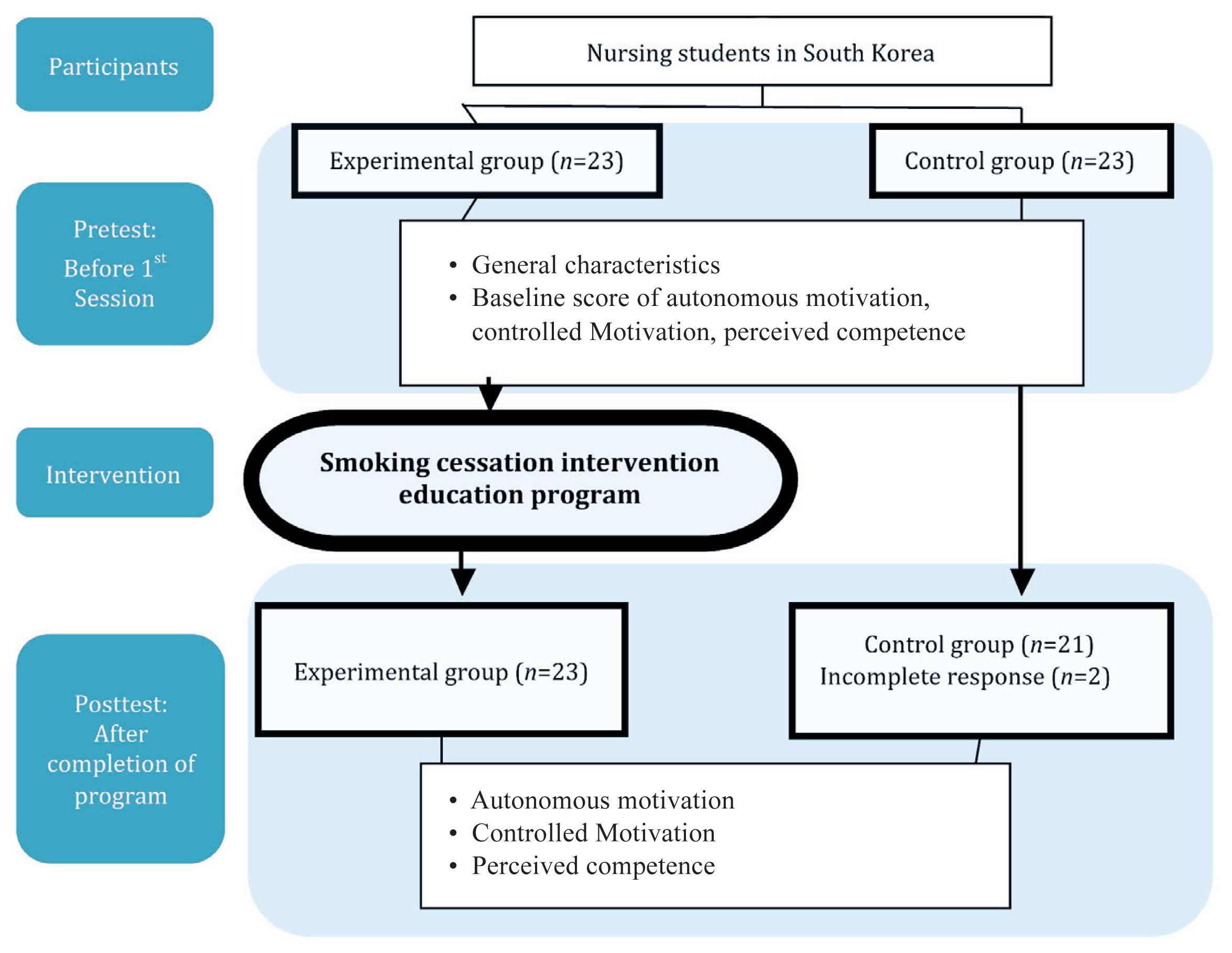

This study was a quasi-experimental design, using a pre–posttest nonequivalent control group, to examine the effects of a smoking cessation intervention education program, based on blended learning for nursing students (Figure 1).

2. Setting and samples

The study was conducted in Busan city, South Korea, and included 44 nursing students. After approval by the relevant institutional review board, study participants were recruited using convenience sampling from 2nd year nursing students on a 4-year baccalaureate university program. The experimental group consisted of 2nd year nursing students enrolled on an elective course entitled “Health Education.” This course was developed to expose undergraduate nursing students to various topics and methods of health education. The control group consisted of students not enrolled in this course.

The researcher informed the students that participation in the smoking cessation intervention education program was required to receive a grade, but data collection using the questionnaire would be voluntary and anonymous. The students were also informed that the data would be used for course improvement and research purposes, and that this process would not affect their grade.

After this information was given, baseline data were collected prior to the 1st session and the post-intervention data collection occurred after completion of the program. A total of 44 individuals participated in the study, 23 in the experimental group and 21 in the control group. Using G*Power version 3.1.7 [15], 2 groups of 21 participants each would provide 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.80, using an independent t test with a significance level of 0.05. With this information considered, a total sample of 42 participants was deemed appropriate.

3. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the institutional review board of the university affiliated to the researchers.

4. Measurements

4.1. Motivation

Motivation was measured using a modified version of the Learning Self-Regulation Questionnaire (SRQ-L) used by students learning to perform medical interviewing; developed by Williams and Deci [16] and revised by the authors to examine nursing students’ motivational processes that underly implementation of smoking cessation interventions with smokers. The SRQ-L contains 3 questions about why participants would engage in learning a smoking cessation intervention. It contains 2 subscales: autonomous motivation (intrinsic motivation) and controlled motivation (external motivation) and consists of 14 items with response options ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). Thus, the responses that were provided were either autonomous or controlled (7 items per subscale for a total of 14). Mean scores were calculated for each subscale, and higher scores denoted more autonomous or controlled motivation. Although controlled motivation was not expected to be affected by the smoking cessation intervention education program, it was measured in the SRQ-L, and was thus included in the reported results. In a previous study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.83 for autonomous motivation and 0.80 for controlled motivation [7], whilst the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the present study was 0.84 for autonomous motivation and 0.81 for controlled motivation.

4.2. Perceived competence

Perceived competence was measured using a version of the Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) developed by Williams and Deci [16] and revised by the authors, so that it was appropriate for determining the degree to which participants felt capable of engaging in smoking cessation interventions with smokers. A total of 4 items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much). Higher mean scores indicated a higher perceived level of competence to implement smoking cessation interventions. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.91 for perceived competence in a previous study [7], whilst the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for perceived competence in the present study was 0.90.

5. Data collection

Data were collected from October 23, 2017 to November 27, 2017. When participants filled out the questionnaire, they also provided their birth year, and the last 4 digits of their mobile phone number. This information was used to match the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires. The pretest was conducted to examine the homogeneity of the participants, and to measure baseline autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and perceived competence in performing a smoking cessation intervention. The pretest was completed before starting the 1st session, and the posttest was performed after completion of the program, using the same questionnaire that was used for the pretest. Pretest and posttest questionnaires were administered at the same time for the control group.

6. Educational intervention

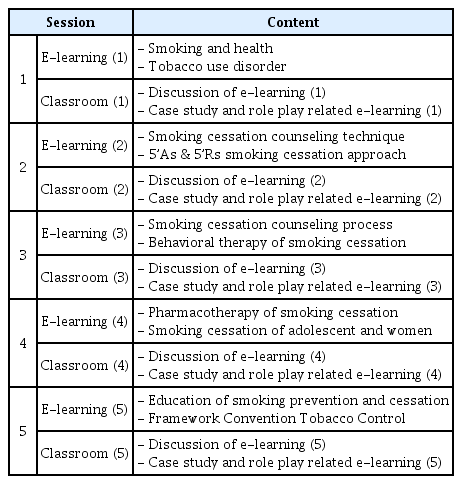

The smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning, consisted of an e-learning program and a face-to-face learning program. The e-learning program of a smoking cessation intervention was developed by the Korea Health Promotion Institute [17]. This web-based e-learning program consisted of 10 courses, each 30-minutes long: “Smoking and health,” “Tobacco use disorder,” “Smoking cessation counseling technique,” “5 A’s & 5 R’s smoking cessation approach,” “Smoking cessation counseling process,” “Behavioral therapy of smoking cessation,” “Pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation,” “Smoking cessation in adolescents and women,” “Education in smoking prevention and cessation,” and “Framework convention tobacco control.” Following confirmation through several in-depth discussions among the authors on the applicability of the face-to face learning program within a nursing education program, the face-to face learning program consisted of 5 courses of case studies and role plays related to e-learning, each course was 60-minutes long. The face-to-face learning program of the smoking cessation intervention education program, aimed to familiarize students with smoking cessation interventions by presenting them with various cases. In addition, it allowed them to indirectly experience a successful smoking cessation intervention through case studies and provided them with the opportunity to review the educational content (Table 1).

After obtaining written informed consent, the smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning was administered to the experimental group in 5 sessions, consisting of 2 courses of an e-learning program and 1 course of a face-to-face learning program per session. The participants in the experimental group studied 2 courses of the e-learning program on their own in advance of the face-to-face learning program and received 1 course of the face-to-face learning program with materials a week later in each session. The program was implemented to promote the participants’ autonomous motivation and perceived competence to perform a smoking cessation intervention through an interactive e-learning and face-to-face learning program once a week for 5 weeks. In this study, the control group received the opportunity to receive the e-learning program and the face-to-face learning program materials after completing the smoking cessation intervention education program.

7. Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL). To test homogeneity, chi-square test and t test were used. To examine the effects of the smoking cessation intervention program between the 2 groups, t test of the mean differences (i.e., posttest minus pretest scores) were used. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

1. Participants’ characteristics and baseline comparison

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics and the main variables of all participants. No significant differences in characteristics were found between the experimental and control groups. In both groups, most participants were female (experimental group: 78.3%; control group: 81.0%), nonsmokers (experimental group: 82.6%; control group: 81.0%) and reported no disease (experimental group: 87.0%; control group: 90.5%). In addition, no statistically significant differences were observed between the 2 groups regarding the baseline mean scores of autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and perceived competence in performing a smoking cessation intervention. Therefore, the 2 groups were considered homogenous.

2. Effects of the smoking cessation intervention education program

An independent t test of mean differences (posttest score minus pretest score) showed that there were significant differences in autonomous motivation (t = 6.882, p < 0.001), controlled motivation (t = 3.729, p = 0.001), and perceived competence (t = 3.801, p < 0.001) between the 2 groups (Table 3). This demonstrated that the smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning produced significant improvements in nursing students’ autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, and perceived competence in performing a smoking cessation intervention.

Discussion

The results in this study showed that a smoking cessation intervention education program adopting blended learning was significantly effective in enhancing nursing students’ autonomous motivation and perceived competence in a smoking cessation intervention. These results are consistent with a previous study that used a 1-group quasi-experimental design, indicating that a SDT-based smoking cessation intervention program consisting of online and offline learning, significantly increased autonomous motivation and perceived competence in nursing students [7]. The most prominent barriers for nursing students were a lack of knowledge and inexperience concerning performance of a smoking cessation intervention [8,18]. The problem might be that students receive insufficient teaching about smoking cessation interventions in their nursing curriculum [18]. In this study, the smoking cessation intervention education program was designed to include not only understanding of smoking cessation interventions such as tobacco use disorder through an e-learning program, but also actual skills to help smokers to quit such as pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy through a face-to–face learning program focused on providing the opportunity for skill acquisition in an elective course of the nursing curriculum. This current study found that blended learning (consisting of e-learning, which promotes self-directed learning, and face-to-face learning, which incorporates instructive feedback in a non-judgmental fashion), enhanced autonomous motivation and perceived competence through sharing knowledge and experience of a smoking cessation intervention in an autonomous-supportive learning environment. This is in line with other studies that explore the impact of SDT-based programs on the adaptation and maintenance of new health-related behaviors and interviewing, providing empirical evidence that the optimal motivational profile for sustained behavior change is one of high autonomous motivation and high perceived competence [19,20]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to provide smoking cessation intervention education programs for nursing students.

In our study, we speculated that blended learning would elicit a greater increase in autonomous motivation and perceived competence regarding a smoking cessation intervention. This is consistent with the results of previous research, in which nursing students taught with blended learning programs showed higher levels of academic accomplishment such as knowledge and self-efficacy [21]. Nursing clinical education, such as teaching smoking cessation interventions, is complex and requires a multifaceted approach to address nursing students [8]. In the current study, the blended learning enabled external knowledge of the smoking cessation intervention to be internalized, enhanced the development of a range of nursing clinical competencies, developed problem-solving strategies, and promoted critical reflective thinking about the smoking cessation intervention [13]. Furthermore, blended learning can be a good tool for enhancing the quality of nursing education, despite the limited nursing curriculum time. Smoking continues to be a major public health problem and improving smoking cessation intervention training is a recognized public health priority [22]. Therefore, it is important that smoking cessation intervention education programs in undergraduate nursing should include a whole spectrum of interventions with specific details to enable adoption of learner-centered teaching programs.

This study revealed that participants in the experimental group also experienced an increase in controlled motivation that involved feeling pressured by external sources to provide a smoking cessation intervention. Because our smoking cessation intervention education program did not target controlled motivation and was intended to be non-pressuring and supportive of autonomy, this result was unexpected and is consistent with the findings of another study [7]. Simply incorporating smoking cessation content into the course, presumably conveyed to students that the professors believed it was important [7]. Furthermore, when a new guideline is first introduced, since most are not intrinsically enjoyable, healthcare providers may feel pressure from external demands [23]. Over time, individuals may internalize the value of the guideline and experience a greater sense of autonomy [24]. Since this study was performed over a relatively short period of time, it is possible that the increase in controlled motivation reflected the fact that students were relatively early in the internalization process and considered smoking cessation as a “must-do.” Therefore, internalization of new skills, such as a smoking cessation intervention, may require more time, supportive feedback from peers and tutors, and reflection on learning [25].

The findings in this study contribute to the current body of knowledge that supports the effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention education programs for nursing students. The usefulness of this program in nursing education will need further testing, including longitudinal assessments of the potential effects of the smoking cessation intervention education program on students’ motivation and competence to perform smoking cessation interventions with smokers.

The limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. A convenience sampling method was used in the experimental group, rather than random assignment, which may have introduced selection bias into the study because experimental group members who chose health education in the elective course may have had greater interest in and motivation for learning a smoking cessation intervention. This study did not examine the long-term effects after finishing the smoking cessation intervention education program based on blended learning or test their actual performance with an objective structured clinical examination. Additionally, the extent to which this intervention would be effective in other settings warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, the integration and evaluation of smoking cessation intervention education programs, including those based on blended learning, are recommended as a means to facilitate students’ confidence and motivation to consistently engage in smoking cessation. Through blended learning-based training, nursing students may perform the intervention better and accept smoking cessation interventions as a part of standard nursing care. Finally, blended learning improved the nursing students’ autonomous motivation and perceived competence so that they could provide a smoking cessation intervention to smokers in clinical situations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by 2017 Youngsan University research fund.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interests to declare